Deflation returns to Japan. Tyler Cowen has a thoughtful Marginal Revolution post, expressing puzzlment. Scott Sumner discussion here, and Financial Times coverage.

Let's look at the bigger picture. Here is the discount rate, 10 year government bond rate and core CPI for Japan. (CPI data here if you want to dig.)

If you parachute down from Mars and all you remember from economics is the Fisher equation, this looks utterly sensible. Expected inflation = nominal interest rate - real interest rate. So, if you peg the nominal interest rate, inflation shocks will slowly melt away. Most inflation shocks are individual prices that go up or down, and then it takes some time for the overall price level to work itself out.

The recent experience looks a lot like 1998. As of 2001, it would have been reasonable to think that the dreaded deflationary vortex was going to break out. But it didn't. Inflation came trundling back. As of 2008, you might have thought that low rates would finally spark inflation. But they didn't. In 2014-2015 you might have thought that the latest in a 20-year string of fiscal stimuli, bond purchases, bridges to nowhere and xx-onomics programs were finally going to produce inflation. But, so far at least, no.

It's tough to make predictions, especially about the future, as the late great Yogi Berra reminds us. Still, this is the third strike.

The long term bond market continued its linear trend throughout the recent episode, a strong sign that expected inflation had not moved. And the sharp jump up and then back down again exactly a year later smacks of data errors, or one specific component. I hope a commenter has more patience for wading through the data than I do to find it.

To be sure, Tyler emphasizes a central puzzle. Even if you accept the view that the Fisher equation is a stable steady state, that ties down expected inflation, but not actual inflation. There are troublesome multiple equilibria. The fiscal theory of the price level can tie down one equilibrium in theory, but not yet in practical application. But I wonder if we're not overblowing this problem. If we interpret the shocks not as shocks to individual prices that take time to melt away, but as expectational shocks, we still get a pretty good view of the data. Nominal interest rates plus a slowly time-varying real rate tie down expected inflation, little multiple equilibrium shocks let actual inflation vary, but such shocks melt away.

And the earthquake fault under all of this: Even the theory that says pegs can be stable warns they can only be stable if bond investors think they will be paid back. At some point -- 250% debt to gdp, slow growth and no population growth? 300%? What does it take? -- they change their minds. And then Japan gets the inflation it has so long desired, and a bit more to boot.

In the meantime, perhaps rather than worry-worry, we should celebrate 20 years of the optimum quantity of money, achieved at last.

Update David Beckworth on the same topic. I'm less of a NGDP target fan. It's like saying all the Chicago Cubs need is a "win the world series" target. OK, but what do you want them actually to do differently? What 3 trillion of QE wasn't enough, but 6 will do the trick? I know the answer, that talk alone tweaks some off equilibrium paths to generate more "demand" today. And monetary policy does seem to be just talk these days. But still... I'm also less of a fan of looking at monetary aggregates. At zero rates, money = bonds, and MV=PY becomes V = PY/M. But it's a well stated analysis in these terms, and nice coverage of the fiscal theory at the end.

Senin, 28 September 2015

Rabu, 23 September 2015

After the ACA

After the ACA, a longish essay on what to do instead of Obamacare. Relative to the policy obsession with health insurance, it focuses more on the market for health care, and relative to the usual focus on demand -- people paying with other people's money -- it focuses on supply restrictions. Paying with your own money doesn't manifest a cab on a rainy Friday afternoon, if you face supply restrictions.

Long time blog readers saw the first drafts. Polished up, it is published at last in the volume The Future of Healthcare Reform in the United States edited by Anup Malani and Michael H. Schill, just published by the University of Chicago Press.

The rest of the volume is interesting, and the conference was enlightening to me, a part-timer in the massive health-policy area. As the U of C press puts it with perhaps unintentional wry wit: "By turns thought-provoking, counterintuitive, and even contradictory, the essays together cover the landscape of positions on the PPACA's prospects."

PART 1. ACA and the Law

Chapter 1. Postmortem on NFIB v. Sebelius: Early Reflections on the Decision That Kept the ACA Alive. Carter G. Phillips and Stephanie P. Hales

Chapter 2. Federalism, Liberty, and Risk in NFIB v. Sebelius. Aziz Z. Huq

Chapter 3. The Future of Healthcare Reform Remains in Federal Court. Jonathan H. Adler

Chapter 4. Essential Health Benefits and the Affordable Care Act: Law and Process. Nicholas Bagley and Helen Levy

PART 2. ACA and the Federal Budget

Chapter 5. The Fiscal Consequences of the Affordable Care Act. Charles Blahous

Chapter 6. Estimating the Impact of the Demand for Consumer-Driven Health Plans Following the 2012 Supreme Court Decision of the Constitutionality of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Stephen T. Parente

PART 3. ACA and Healthcare Delivery

Chapter 7. After the ACA: Freeing the Market for Healthcare. John H. Cochrane

Chapter 8. Obamacare and the Theory of the Firm. Einer Elhauge

Chapter 9. Can Federal Provider Payment Reform Produce Better, More Affordable Healthcare Meredith B. Rosenthal

PART 4. Healthcare Costs, Innovation, and ACA

Chapter 10. The Role of Technology in Expenditure Growth in Healthcare. Amitabh Chandra and Jonathan Holmes

Chapter 11. Economic Issues Associated with Incorporating Cost- Effectiveness Analysis into Public Coverage Decisions in the United States. Anupam B. Jena and Tomas J. Philipson

Chapter 12. The Complex Relationship between Healthcare Reform and Innovation. Darius Lakdawalla, Anup Malani, and Julian Reif

PART 5. ACA and Health Insurance Markets

Chapter 13. The Affordable Care Act and Commercial Health Insurance Markets: Fixing What’s Broken? James B. Rebitzer

Chapter 14. A Cautionary Warning on Healthcare Exchanges: A Plea for Deregulation. Richard A. Epstein

Long time blog readers saw the first drafts. Polished up, it is published at last in the volume The Future of Healthcare Reform in the United States edited by Anup Malani and Michael H. Schill, just published by the University of Chicago Press.

The rest of the volume is interesting, and the conference was enlightening to me, a part-timer in the massive health-policy area. As the U of C press puts it with perhaps unintentional wry wit: "By turns thought-provoking, counterintuitive, and even contradictory, the essays together cover the landscape of positions on the PPACA's prospects."

PART 1. ACA and the Law

Chapter 1. Postmortem on NFIB v. Sebelius: Early Reflections on the Decision That Kept the ACA Alive. Carter G. Phillips and Stephanie P. Hales

Chapter 2. Federalism, Liberty, and Risk in NFIB v. Sebelius. Aziz Z. Huq

Chapter 3. The Future of Healthcare Reform Remains in Federal Court. Jonathan H. Adler

Chapter 4. Essential Health Benefits and the Affordable Care Act: Law and Process. Nicholas Bagley and Helen Levy

PART 2. ACA and the Federal Budget

Chapter 5. The Fiscal Consequences of the Affordable Care Act. Charles Blahous

Chapter 6. Estimating the Impact of the Demand for Consumer-Driven Health Plans Following the 2012 Supreme Court Decision of the Constitutionality of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Stephen T. Parente

PART 3. ACA and Healthcare Delivery

Chapter 7. After the ACA: Freeing the Market for Healthcare. John H. Cochrane

Chapter 8. Obamacare and the Theory of the Firm. Einer Elhauge

Chapter 9. Can Federal Provider Payment Reform Produce Better, More Affordable Healthcare Meredith B. Rosenthal

PART 4. Healthcare Costs, Innovation, and ACA

Chapter 10. The Role of Technology in Expenditure Growth in Healthcare. Amitabh Chandra and Jonathan Holmes

Chapter 11. Economic Issues Associated with Incorporating Cost- Effectiveness Analysis into Public Coverage Decisions in the United States. Anupam B. Jena and Tomas J. Philipson

Chapter 12. The Complex Relationship between Healthcare Reform and Innovation. Darius Lakdawalla, Anup Malani, and Julian Reif

PART 5. ACA and Health Insurance Markets

Chapter 13. The Affordable Care Act and Commercial Health Insurance Markets: Fixing What’s Broken? James B. Rebitzer

Chapter 14. A Cautionary Warning on Healthcare Exchanges: A Plea for Deregulation. Richard A. Epstein

Selasa, 22 September 2015

Thank you for scheduling with our office

One thing I would be asked after scheduling a patient for an appointment on a daily basis was, “Can you email that to me?” My answer always was, “Sure, I will do it right now.” Then I would open up my Microsoft Outlook and manually send the patient an email at his or her request. It was a time-consuming task, but my patients were happy. If we could somehow automate this task, we would have happy patients and happy teams, right?

Well . . . Dentrix eCentral has made this a reality! When you schedule a new patient or an existing patient, the eCentral Communication will send out automated correspondence with all their appointment details. You have the option of sending out a customized email, text message, or postcard. Since you have the option of customizing the email to make it personal for your practice, why not include a link where your new patients can click to be directed to the new patient forms?

These new features sends the Dentrix eCentral Communication manager into overdrive. It makes me excited to see all the new features making a huge impact on the daily lives of the front office team’s efficiency and giving our patients the tools they need to manage their appointments.

CLICK HERE for more information on these exciting new features.

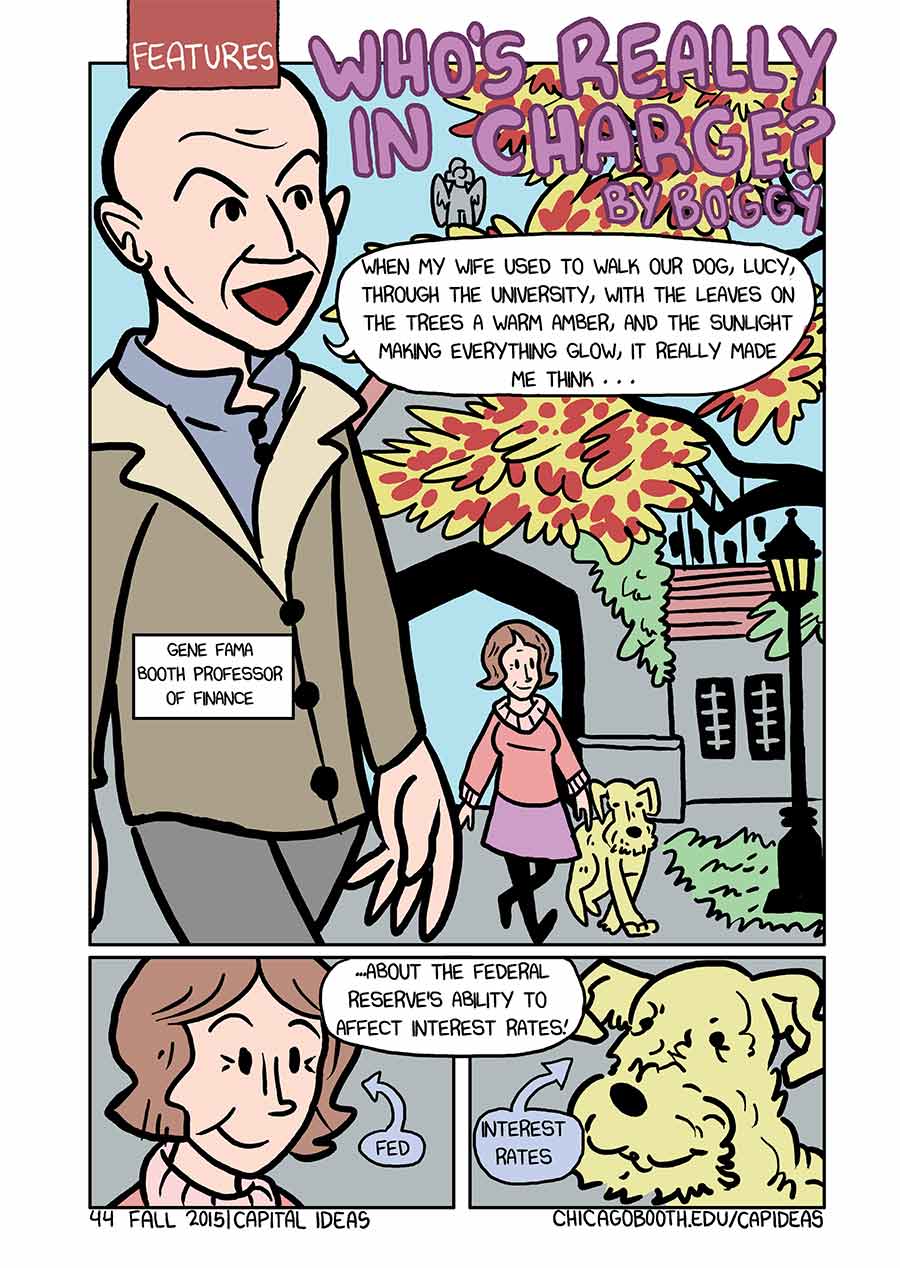

Who is walking who?

Click here for the rest

It's a graphic novel treatment of Gene Fama's Does the Fed Control Interest Rates? paper, from the Booth school's Capital Ideas magazine, by Eric Cochrane (yes, we're related). If it appears squished, use a wide browser window. The art is better in the printed form.

Eric captured cointegration and error correction, and Gene's regressions of short and long-term interest rates, cleverly with the story. Does Sally take Lucy for a walk, or is Lucy really leading Sally around? Well, when Lucy goes off hunting for a squirrel, who then moves to catch up?

Minggu, 20 September 2015

Why do I need encrypted email?

Let’s picture a postcard. This mode of communication is perfect for documenting your latest trip laden with landmark pictures on the front and a simple “Wish you were here” written on the back. Anyone can flip over the postcard, read your sentiments. You’d never write anything too personal knowing this postcard can be an open book. No need to safeguard this innocent letter.

Let’s picture a postcard. This mode of communication is perfect for documenting your latest trip laden with landmark pictures on the front and a simple “Wish you were here” written on the back. Anyone can flip over the postcard, read your sentiments. You’d never write anything too personal knowing this postcard can be an open book. No need to safeguard this innocent letter.Now imagine if it has your social security number written on the back under your name. Not so innocent anymore! This is exactly what an email is. A regular email is open for anyone to view while in transit to its recipient. Now imagine a letter, duct taped and carried by an armored van to the recipient. This is an encrypted email.

As a Covered Entity, you are responsible, by HIPAA law, for safeguarding your patient’s data.

Anytime electronic Protected Health Information (ePHI) is being sent in an email, HIPAA recommends implementing procedures to ensure secure transmission and storage. The easiest way to do this is to utilize an encrypted email system.

Ideally, look for a provider that offers the option to send regular vs. encrypted mail. For example with Aspida Mail it is triggered by a keyword, encrypt in the subject or body of an email. If that keyword is omitted, all emails flow as usual.

Additionally, if you are receiving ePHI to your email, verify you are implementing secure storage procedures. Typically, (free) Gmail, Aol & Yahoo Mail do not store securely.

Additionally, if you are receiving ePHI to your email, verify you are implementing secure storage procedures. Typically, (free) Gmail, Aol & Yahoo Mail do not store securely.

Additional Tips:

- Opening Emails

- Use a mail solution that has antivirus and a robust spam filter enabled.

- Inspect all email messages thoroughly, including the senders address.

- Do not open any email that looks suspicious. If you do not know the sender, treat it as suspicious email.

- Sending Emails

- Confirm the email address with which you are sending information.

- Do not put any ePHI in the subject line of an encrypted email – this information is still transmitted through an unsecure environment.

By familiarizing yourself and your team about these email procedures, you’ve taken the first steps to protection. The next step would be to figure out what works best for your practice and come up with a plan for implementation. And don’t forget, documentation of all policies and procedures is key!

CLICK HERE for more info on Aspida email solutions

About the Author:

Laura Miller is Compliance Manager of Aspida, has quickly established itself as an industry leader in providing compliance security products and services for healthcare providers.

Jumat, 18 September 2015

Is the Fed Pulling or Pushing?

I did a little interview with Mary Kissel of the Wall Street Journal, following up on thursday's oped. Mary is, as you can tell, a well-informed interviewer and asks some tough questions. She did a great job of pushing hard on the usual Wall Street wisdom about how the Fed, though it has not done anything but talk in years, is secretly behind every gyration of stock or housing prices.

The central point came to me hours later, as it usually does. Is the Fed in fact "holding down" interest rates? Is there some sort of natural market equilibrium that features higher rates now, but the Fed is pushing down rates? That's the conventional view, clearly expressed in Mary's questions.

Well, let's think about that. If a central bank were holding down rates, what would it do? Answer, it would lend a lot of money at low rates. Money would be flowing out the discount window (that's where the Fed lends to banks), to banks, and through banks to the rest of the economy, flooding the place with low-rate loans. The interest rate the Fed pays on reserves and banks pay to borrow from the Fed would be low compared to market rates; credit and term spreads would be large, as the Fed would be trying to drag down those market rates.

That is, of course, the exact opposite of what's happening now. Banks are lending the Fed about $3 trillion worth of reserves, reserves the banks could go out and lend elsewhere if the market were producing great opportunities. Spreads of other rates over the rates banks lend to or borrow from the Fed are very low, not very high. Deposits are flooding in to banks, not loans out of banks.

If you just look out the window, our economy looks a lot more like one in which the Fed is keeping rates high, by sucking deposits out of the economy and paying banks more than they can get elsewhere; not pushing rates down, by lending a lot to banks at rates lower than they can get elsewhere.

In reality of course, the Fed isn't doing that much of anything. Lots of deposits (saving) and a dearth of demand for investment (borrowing) drives (real) interest rates down, and there is not a whole lot the Fed can do about that. Except to see the parade going by, grab a flag, jump in front and pretend to be in charge.

Kamis, 17 September 2015

Top 5 things to bring the miracle of technology to life

During my 22 years in dentistry, I have been both the trainer and the trainee when it comes to implementing new technology in the dental practice. People who know me see me as kind of a computer geek.

During my 22 years in dentistry, I have been both the trainer and the trainee when it comes to implementing new technology in the dental practice. People who know me see me as kind of a computer geek.The satisfaction of getting a new computer, network or piece of technology to work was the thrill of the hunt. It’s amazing sometimes that it all works together.

The miracle that all the technology works together is actually not a miracle at all—it takes planning and professional help. It doesn’t just happen. There are five critical things to consider when purchasing a new piece of technology, whether it is for the clinical or business side of your practice. These five things will not only help bring this miracle to life but also make sure your team is as efficient as it can be:

CLICK HERE to continue reading my full article on DPR

Rabu, 16 September 2015

WSJ oped, director's cut

WSJ Oped, The Fed Needn’t Rush to ‘Normalize’ An ungated version here via Hoover.

Teaser:

Yes, I'm aware of recent empirical work that QE has some effect:

And the whole Neo-Fisherian question got left on the cutting room floor too. But if a 0% interest rate peg is stable, then so is a 1% interest rate peg. It follows that raising rates 1% will eventually raise inflation 1%. New Keynesian models echo this consequence of experience. And then the Fed will congratulate itself for foreseeing the inflation that, in fact, it caused.

I didn't go so far as to advocate this, back in draft mode. I don't like the way so many economists have a pet theory and rush to Washington to ask that it be implemented. But given that just how monetary policy works is so uncertain, a robust policy choice ought to put at least some weight on such a cogent view.

The word "normal" has many connotations. John Taylor likes return to "normal," meaning return to something like a Taylor rule. When the Fed says "normal," I sense they simply mean higher nominal interest rates, and a smaller balance sheet, but continuing lots of talk and lots of discretion. The "normal" I'm dubious of in the oped is the latter version.

Teaser:

The outcomes we desire from monetary policy are about as good as one could hope. Inflation is low and steady. Interest rates are lower than Americans have seen in generations. Unemployment, at 5.1%, has recovered to near normal. And banks and businesses sitting on huge piles of cash don’t go bust, a boon to financial stability.Opeds are real Haikus -- 950 words is torture for me. So lots of good stuff got left on the cutting room floor, especially acknowledgement of objections and criticisms.

Yes, economic growth is too slow, too many Americans have dropped out of the workforce, earnings are stagnant, and the country faces other serious challenges. But monetary policy can’t solve long-term structural problems.

Yes, I'm aware of recent empirical work that QE has some effect:

Even the strongest empirical research argues that QE bond buying announcements lowered rates on specific issues a few tenths of a percentage point for a few months. But that's not much effect for your $3 trillion. And it does not verify the much larger reach-for-yield, bubble-inducing, or other effects.Yes, I'm aware of lots of theory going on:

An acid test: If QE is indeed so powerful, why did the Fed not just announce, say, a 1% 10 year rate, and buy whatever it takes to get that price? A likely answer: they feared that they would have been steamrolled with demand. And then, the markets would have found out that the Fed can’t really control 10 year rates. Successful soothsayers stay in the shadows of doubt.

Granted, economic theories are always in flux. Advocates are ready with after-the-fact patches for traditional theories’ failures. Maybe wages are eternally "sticky" downward, so deflation spirals can't happen. Never mind. Also, researchers are busy adding “frictions” to modern models to try to make them generate huge QE effects. But for policy-making, all of this is new, hypothetical and untested.We lost an important warning

Economic theories are useful for working out logical connections. The forward-looking [new-Keynesian] theory predicts that an interest rate peg is only stable if fiscal policy is solvent, so people trust government debt. Past interest rate pegs have fallen apart when their governments ran in to fiscal problems. That’s an important warning.And we lost a lot of nice metaphors

The deflationary spiral story posits that the economy is inherently unstable, like a broom being held upside down. The Fed must actively move interest rates around, as you move the bottom of a broom to keep it toppling over. But when interest rates hit zero, the Fed could no longer adjust interest rates. The broom should have tipped over. The lesson is clear: In fact, our economy is stable. Small movements of inflation will melt away on their own. The Fed does not need constantly to adjust interest rates to avoid “spirals.”Later,

This forward-looking (new-Keynesian) theory predicts inflation is stable because it assumes that people are smart, and look ahead. Traditional theories assume that people form their views of the future mechanically from the past. Yes, if you try to drive a car while looking in the rear view mirror, your driving will be unstable, and a Fed sitting in the right seat telling you where to go would help. But if people look out the front window, cars stably converge to the road without direction.And on theory vs. practice

As Ben Bernanke wisely noted, “The problem with QE is that it works in practice, but it doesn’t work in theory.” That’s a big problem. If we have no theory why something works, then maybe it doesn’t really work. Doctors long saw that bleeding worked in practice— they bled patients, patients got better — but had no theory for it.I also had a lot more on the wonders of living the optimal quantity of money. $3 trillion of reserves means 100% reserve deposits are sitting before us. No inflation means no inflation-induced distortions of the tax code. You don't pay capital gains taxes on inflation, or return taxes on the component of return due to inflation. But all that will wait for the next one, I guess.

And the whole Neo-Fisherian question got left on the cutting room floor too. But if a 0% interest rate peg is stable, then so is a 1% interest rate peg. It follows that raising rates 1% will eventually raise inflation 1%. New Keynesian models echo this consequence of experience. And then the Fed will congratulate itself for foreseeing the inflation that, in fact, it caused.

I didn't go so far as to advocate this, back in draft mode. I don't like the way so many economists have a pet theory and rush to Washington to ask that it be implemented. But given that just how monetary policy works is so uncertain, a robust policy choice ought to put at least some weight on such a cogent view.

The word "normal" has many connotations. John Taylor likes return to "normal," meaning return to something like a Taylor rule. When the Fed says "normal," I sense they simply mean higher nominal interest rates, and a smaller balance sheet, but continuing lots of talk and lots of discretion. The "normal" I'm dubious of in the oped is the latter version.

Selasa, 15 September 2015

Conundrum Redux

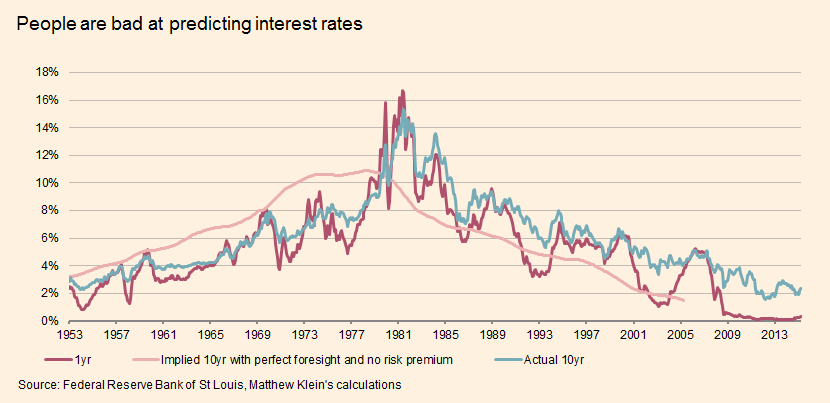

FT's Alphaville has an excellent post by Matthew Klein on long-term interest rates, organized around Greenspan's "conundrum." The "conundrum" was that Greenspan couldn't control long term rates as he wished. Long rates do not always track short rates or Fed pronouncements. As the post nicely shows, it was ever thus.

The following graph from the post struck me as very useful, especially as so much bond discussion tends to have short memories.

If the 10 year rate had followed the pink line, you would not have made any more buying 10 year bonds than buying short term bonds. (The pink line is the forward-looking moving average of the one year rates.)

What the graph shows beautifully, then, is this: Until 1981, long-term bonds were awful. You routinely lost money buying 10 year bonds relative to buying one year bonds. It goes on year in and year out and starts to look like a constant of nature.

From 1981 until today, the actual 10 year rate has been well above this ex-post breakeven rate. It's been a great 35 years for long-term bond investors. That too seems like a constant of nature now.

Of course, inflation going down was good for long term bonds. But we usually don't think there can be surprises in the same direction 35 years in a row.

You can also see the steady 35 year downward trend in 10 year rates. Good luck seeing the "massive" effects of quantitative easing or much of anything else here.

A lot of academic papers are devoted to this risk premium in bonds, including "Decomposing the yield curve" that I wrote with Monika Piazzesi.

It is now routine to decompose the spread between long and short term bonds into an expectations component and a risk premium, with changes in risk premium accounting for "conundrums." It is also routine not to present standard errors of this decomposition. The one thing I know for sure is that there is a lot of uncertainty on that decomposition. Any risk-premium estimate comes down to a bond-return forecasting regression. We know how much uncertainty there is in that exercise.

The following graph from the post struck me as very useful, especially as so much bond discussion tends to have short memories.

If the 10 year rate had followed the pink line, you would not have made any more buying 10 year bonds than buying short term bonds. (The pink line is the forward-looking moving average of the one year rates.)

What the graph shows beautifully, then, is this: Until 1981, long-term bonds were awful. You routinely lost money buying 10 year bonds relative to buying one year bonds. It goes on year in and year out and starts to look like a constant of nature.

From 1981 until today, the actual 10 year rate has been well above this ex-post breakeven rate. It's been a great 35 years for long-term bond investors. That too seems like a constant of nature now.

Of course, inflation going down was good for long term bonds. But we usually don't think there can be surprises in the same direction 35 years in a row.

You can also see the steady 35 year downward trend in 10 year rates. Good luck seeing the "massive" effects of quantitative easing or much of anything else here.

A lot of academic papers are devoted to this risk premium in bonds, including "Decomposing the yield curve" that I wrote with Monika Piazzesi.

It is now routine to decompose the spread between long and short term bonds into an expectations component and a risk premium, with changes in risk premium accounting for "conundrums." It is also routine not to present standard errors of this decomposition. The one thing I know for sure is that there is a lot of uncertainty on that decomposition. Any risk-premium estimate comes down to a bond-return forecasting regression. We know how much uncertainty there is in that exercise.

Unused insurance benefits . . . it's now more than a once a year project

Since I have been writing the Dentrix Office Manager blog, I have posted up an article about this time of year reminding you to reach out to patients who have unscheduled treatment withremaining insurance benefits. This year is no different. However, I think that it might be a project you might want to tackle a couple of times each year depending on when the big employer groups start their benefit year. When I was working in my practice in Washington state, we had several groups that renewed at other times than January. Boeing, for example, renews in July and the school districts renew in October.

If you decide to generate this lists of patients, you can filter the list by benefit renewal month. To generate the report, go to the Appointment Book > Treatment Manager > select the filters you want, including the benefit renewal month.

Since I have written on this topic every year, I am going to point you back to the articles so you don’t have to do a search.

CLICKHERE to read “Don’t let unused insurance benefits go to waste.”

CLICKHERE to read “Unscheduled treatment . . . the urgency is now.”

CLICKHERE to read “Send letters that make an impact”

Senin, 14 September 2015

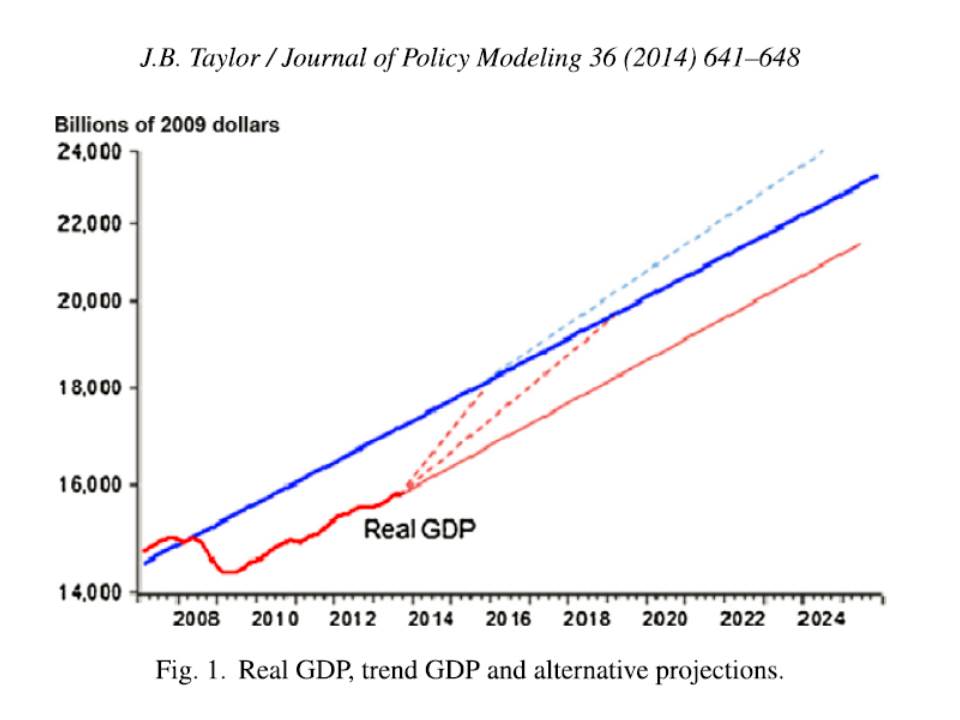

Two for growth

I saw two very nice, short views on growth: John Taylor Can We Restart This Recovery All Over Again? and Andy Atkeson, Lee Ohanian, and William E. Simon, Jr., 4% Economic Growth? Yes, We Can Achieve That.

John gets the art prize

Andy, Lee and William get the boil-it-down-to-basics prose prize

John gets the art prize

Andy, Lee and William get the boil-it-down-to-basics prose prize

Safety-net policies should not discourage work through high implicit tax rates resulting from means-tested programs. Regulatory policies should not erect barriers to competition and raise costs. Education policies should expand competition and reward the most successful teachers. Immigration policies should expand the number of skilled workers and immigrant entrepreneurs. And tax policies should simplify the tax code, reduce business and personal marginal income tax rates and broaden the tax base.

Jumat, 11 September 2015

Sargent on Friedman

I ran across a little gem by Tom Sargent, "The Evolution of Monetary Policy Rules." Alas, it's gated in the JEDC so you'll need a university IP address to read it, and I haven't found a free copy. It's a transcript of a talk, so doesn't have Tom's usual prose polish, but insightful nonetheless.

Milton Friedman, like the rest of us, changed his mind over the course of a lifetime.

Coordinating monetary and fiscal policy:

The rest of the talk is good too, but I've surely exceeded the proper limit for lifting quotes.

Milton Friedman, like the rest of us, changed his mind over the course of a lifetime.

Coordinating monetary and fiscal policy:

...At different times, Friedman advocated two apparently polar opposite recommendations. In Friedman (1948), he proposed the following rule. He recommended to the fiscal authorities that they run a balanced budget over the business cycle. And he said what the monetary authorities should do, whatever the fiscal authority does, is to monetize 100% of government debt. That monetary rule implies that the entire government deficit is going to be financed with money creation. That is it.

It is interesting to contemplate what Friedman׳s monetary policy rule would imply if the fiscal authority chooses to deviate from Friedman׳s fiscal recommendation by running sustained deficits over the business cycle. Friedman׳s monetary rule then throws responsibility for inflation control immediately at the foot of the fiscal authority. Friedman׳s (1948) monetary rule tells the fiscal authority that if it wants stable money, then it better do the right things. If you want a stable price level, you had better recognize that you need a sound fiscal policy, period. The division of responsibilities between monetary and fiscal authorities is clearly and unambiguously delineated. It is a completely clean set of rules. And this is what Friedman advocated until 1960.

Friedman (1960) advocated what looks to be exactly an opposite set of rules for coordinating monetary and fiscal policy. Friedman now advocated that the Federal Reserve, come hell or high water – it is not a Taylor Rule (for technical reasons) – should increase high-powered money, or something close to it, at k-percent a year, where k is the growth rate of the economy. The Fed is told to stick to the k-percent rule no matter what, recession or no recession. Under this rule, the arithmetic of the government budget constraint will force the fiscal authority to balance its budget in a present value sense.

What is beautiful about both sets of rules, the 1948 set and the 1960 set, is that they are both very clear descriptions of the lines between monetary and fiscal policy. But the rules ascribe quite different duties to the monetary [and fiscal! - JC] authority.The line between money and credit

... In his 1960 A Program for Monetary Stability, and also earlier, Friedman embraced the Chicago tradition of 100% reserves for banks, namely, institutions that offer perfect substitutes for government currency. This amounts to setting an iron curtain line between money and credit. Here is the classic Chicago justification: If you want price level stability, you want to prevent shocks that originate in the borrowing and lending markets from impinging on the supply or demand for money. If you want to do that, just do it: 100% reserves basically puts anybody who issues anything that looks like money out of the business of intermediating. But then who intermediates? It would be firms that engage in the business of servicing lenders who are willing to chase higher returns than offered by money by taking term structure and investment risks. That is a socially desirable business, but according to the 100% reserves rule, it is not what banks or the monetary authority should do.Is this waffling? No.

As someone given to qualifying his recommendations, on the very page that he recommends the 100% reserves rule, Friedman cites in a footnote an unpublished paper by Becker (1956) that convinced Friedman that 100% reserves may be exactly the opposite of what you should do. Instead, you should have free banking, but not like Michael Bordo (2014) described in this conference volume. Becker and Friedman really meant free banking. No charters. Free entry. Let anybody issue bank notes if that they want and let the market value them. That is very much like Adam Smith׳s recommendation in the “Wealth of Nations”. In the footnote, Friedman said Becker and Smith might be correct. Then in the text, Friedman proceeded to discuss how you might finance the interest at a market rate that he recommended be paid on those 100% reserves. He said that how you finance those interest payments is an important issue that will affect outcomes.

So even when he recommended one position, Friedman respectfully entertained a diametrically opposed one. Actually, near the end of his professional life, in one of the last papers he wrote with Anna Schwartz, Friedman virtually endorsed free banking, adding some nice words about Hayek (Friedman and Schwartz, 1986).

Again, the reason I mention Friedman׳s shifting positions is that superficially they seem to be diametrically opposed. They are united at a deeper level by their respect for government inter-temporal budget constraints and their clear division of responsibilities. They are very clear proposals. They’re not ambiguous. They are definite rules. You do not need a dynamic stochastic general equilibrium model to write them down or describe them. But technically, in the instructions to monetary authorities and regulators, they seem to be opposite.

Notice that Friedman does not recommend adopting “something in the middle” – that would confuse issues and only expand a mischievous role for exceptions and “judgment”.

What I take away from all of this is that if Milton Friedman thought that these are tough questions to decide, then they probably are. And they are not going to go away. And if Milton Friedman chose to spend a lot of time thinking about them, then they are probably very important problems to study and resolve.

The rest of the talk is good too, but I've surely exceeded the proper limit for lifting quotes.

Kamis, 10 September 2015

Cheaper sugar

A nice trade epigram from David Henderson

Nothing new. It's in Adam Smith. But nicely expressed. Economics needs good stories.

I don't think Trump understands that when we open trade to other countries, we gain not just as exporters but as consumers. But then, what U.S. politician running for president does? Marco Rubio? Rubio argued a few years ago that he would favour getting rid of quotas on sugar imports if we got something in return. But we do get something in return: it's called cheaper sugar. And getting cheaper sugar, by the way, might have caused LifeSavers not to move from Michigan to Quebec.David might have added, we also get more exports automatically without political deals. When other countries sell us sugar, they get dollars, of every single one ends up buying US exports or invested in the US.

Nothing new. It's in Adam Smith. But nicely expressed. Economics needs good stories.

Sabtu, 05 September 2015

Greece and Banking, the oped

|

| Source: Wall Street Journal; Getty Images |

Local pdf here.

Greece's Ills [and, more importantly, the Euro's] Require a Banking Fix

Greece suffered a run on its banks, closing them on June 29. Payments froze and the economy was paralyzed. Greek banks reopened on July 20 with the help of the European Central Bank. But many restrictions, including those on cash withdrawals and international money transfers, remain. The crash in the Greek stock market when it reopened Aug. 3 reminds us that Greece’s economy and financial system are still in awful shape.

Greece’s banking crisis revealed the main structural problem of the eurozone: A currency union must isolate banks from sovereign debt. To fix this central structural problem, Europe must open its nation-based banking system, recognize that sovereign debt is risky and stop letting countries use national banks to fund national deficits.

If Detroit, Puerto Rico or even Illinois defaults on its debts, there is no run on the banks. Why? Because nobody dreams that defaulting U.S. states or cities must secede from the dollar zone and invent a new currency. Also, U.S. state and city governments cannot force state or local banks to lend them money, and cannot grab or redenominate deposits. Americans can easily put money in federally chartered, nationally diversified banks that are immune from state and local government defaults.

Depositors in the eurozone don’t share this privilege. A Greek cannot, without a foreign address, put money in a bank insulated from the Greek government and its politics. When Greece’s banks fail, international banks can’t step in to offer safe banking services independently of the Greek government.

European bank regulations encourage banks to invest heavily in their own country’s bonds, even when they have lousy ratings. The flawed banking architecture of Europe’s currency union pretends that sovereign default will never happen. Wise Europeans have known about these flaws for years, but the system was never fixed because it allows indebted countries to finance large debts.

This is the euro’s central fault. A currency union must treat sovereign default just like corporate or household default: Defaulters do not leave the currency union, and banks must treat sovereign debt cautiously. When Europeans can put their money into well-diversified pan-European banks, protected from interference from national governments, inevitable sovereign defaults will not spark runs, or destroy local banks and economies. And government bailouts will be far less tempting.

That is the long-term fix, but how does the eurozone get out of its current mess? The ECB’s latest Greek bailout deal is focused on long-run structural reforms, asset sales, budget targets and illusory tax increases. It might at best revive growth in a year or so.

But without well-functioning banks, Greece’s economy will collapse long before such growth arrives. To revive the banks and the economy, Greeks must know their money is safe, now and in the future. So safe that Greeks put money back in the banks, pay debts and seamlessly make payments—with no chance of a euro exit, tightened capital controls that impede international payments or depositor “bail-ins,” a polite word for the government grabbing deposits.

The United States offers a precedent. The U.S. economy ground to a standstill in the banking panic of 1933. The administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt closed America’s banks with a national banking holiday to stem the bank run. It then took immediate steps to restore confidence with the clear promises of the Emergency Banking Act of 1933 to resolve insolvent banks, promises backed up by the remarkable rhetoric of FDR’s first fireside chat and the intact borrowing power of the federal government. When banks reopened, Americans lined up to redeposit their money. In the 1980s, the U.S. deregulated banks to allow extensive branch and interstate banking, further isolating local banks from local troubles.

Europe is headed toward bailing out both the Greek government and Greece’s struggling banks. Instead, Europe should resolve and recapitalize the banks alone, put them under private European ownership and control, and insulate them from further Greek government interference. Then Europe can let Greece default, if need be, without another bank run.

Then move on to Italian and Spanish banks, which are similarly larded up with government debts and are threatening the euro. These banks can still be defused slowly, selling their government debts, without huge bailouts.

Europe needs well-diversified, pan-European banks, which must treat low-grade government debt just as gingerly as they treat low-grade corporate debt. Call it a banking union, or, better, open banking. The Greek tragedy can serve to revive the long-dormant but necessary completion of Europe’s admirable common-currency project.

Kamis, 03 September 2015

Historical Fiction

Steve Williamson has a very nice post "Historical Fiction", rebutting the claim, largely by Paul Krugman, that the late 1970s Keynesian macroeconomics with adaptive expectations was vindicated in describing the Reagan-Volker era disinflation.

The claims were startling, to say the least, as they sharply contradict received wisdom in just about every macro textbook: The Keynesian IS-LM model, whatever its other virtues or faults, failed to predict how quickly inflation would take off in the 1970, as the expectations-adjusted Phillips curve shifted up. It then failed to predict just how quickly inflation would be beaten in the 1980s. It predicted agonizing decades of unemployment. Instead, expectations adjusted down again, the inflation battle ended quickly. The intellectual battle ended with rational expectations and forward-looking models at the center of macroeconomics for 30 years.

Just who said what in memos or opeds 40 years ago is somewhat of a fodder for a big blog debate, which I won't cover here.

Steve posted a graph from an interesting 1980 James Tobin paper simulating what would happen. This is a nicer source than old memos or opeds from the early 1980s warning of impeding doom. Memos and opeds are opinions. Simulations capture models.

The graph:

I thought it would be more effective to contrast this graph with the actual data, rather than rely on your memories of what happened.

The black lines are the Tobin simulation. The blue lines are what actually happened. (I'm not good enough with photoshop to superimpose the graphs, so I read Tobin's data off his chart.)

The two curves parallel in 81 to 83, with reality moving much faster. But In 1984 it all falls apart. You can see the "Phillips curve shift" in the classic rational expectations story; the booming recovery that followed the 82 recession.

And you can see the crucial Keynesian prediction error: After the monetary tightening is over in 1986, no, we do not need years and years of grinding 10% unemployment.

So, conventional history is, it turns out, right after all. Adaptive-expectations ISLM models and their interpreters were predicting years and years of unemployment to quash inflation, and it didn't happen.

One can debate 1981 to 1983. Here reality followed the general pattern, moving down a Phillips curve. Perhaps that is the success. But the move was much quicker than Tobin's simulation. One might crow that inflation was conquered much more quickly than Keynesians predicted. But perhaps the actual monetary contraction may have been larger than what Tobin assumed, and assuming a harsher contraction would have sent the economy down the same curve faster?

Tobin describes his simulation thus:

Now, let's be fair to Tobin. Yes, as quoted by Steve, he came out in favor of "Incomes policies," which used to be a nice euphemism for wage and price controls, but have an even more Orwellian ring these days. But Tobin also wrote, just following this graph,

You can see Tobin clearly seeing the possibilities, and clearly seeing the conclusions that we would come to after seeing the "happier outcome." That he had not come to these conclusions before the fact is understandable.

That contemporary commentators should forget or obfuscate this history, in an effort to resuscitate a comfortable, politically convenient, but failed economics of their youth, is less forgivable.

I don't want to fully endorse the classic resolution of 1984. Lots of other things changed, in particular deregulation and a big tax reform in the air. There was a lot of new technology. Financial deregulation was kicking in. We may find someday that such "supply side" changes were behind the 1980s boom. And we may jettison or radically reunderstand the Phillips curve, even with the free expectations parameter to play around with. It certainly has fallen apart lately (here, here and many more). But ISLM / adaptive expectations as an eternal truth just doesn't hold up. It really did fail in the 70s, and again in the 80s.

PS: The chart using actual inflation FYI

The claims were startling, to say the least, as they sharply contradict received wisdom in just about every macro textbook: The Keynesian IS-LM model, whatever its other virtues or faults, failed to predict how quickly inflation would take off in the 1970, as the expectations-adjusted Phillips curve shifted up. It then failed to predict just how quickly inflation would be beaten in the 1980s. It predicted agonizing decades of unemployment. Instead, expectations adjusted down again, the inflation battle ended quickly. The intellectual battle ended with rational expectations and forward-looking models at the center of macroeconomics for 30 years.

Just who said what in memos or opeds 40 years ago is somewhat of a fodder for a big blog debate, which I won't cover here.

Steve posted a graph from an interesting 1980 James Tobin paper simulating what would happen. This is a nicer source than old memos or opeds from the early 1980s warning of impeding doom. Memos and opeds are opinions. Simulations capture models.

The graph:

|

| Source: James Tobin, BPEA. |

The two curves parallel in 81 to 83, with reality moving much faster. But In 1984 it all falls apart. You can see the "Phillips curve shift" in the classic rational expectations story; the booming recovery that followed the 82 recession.

And you can see the crucial Keynesian prediction error: After the monetary tightening is over in 1986, no, we do not need years and years of grinding 10% unemployment.

So, conventional history is, it turns out, right after all. Adaptive-expectations ISLM models and their interpreters were predicting years and years of unemployment to quash inflation, and it didn't happen.

One can debate 1981 to 1983. Here reality followed the general pattern, moving down a Phillips curve. Perhaps that is the success. But the move was much quicker than Tobin's simulation. One might crow that inflation was conquered much more quickly than Keynesians predicted. But perhaps the actual monetary contraction may have been larger than what Tobin assumed, and assuming a harsher contraction would have sent the economy down the same curve faster?

Tobin describes his simulation thus:

The story is as follows: beginning in 1980:1 the government takes monetary and fiscal measures that gradually reduce the quarterly rate of increase of nominal income, MV. It is reduced in ten years from 12 percent a year to the noninflationary rate of 2 percent a year, the assumed sustainable rate of growth of real GNP. The inertia of inflation is modeled by the average of inflation rates over the preceding eight quarters. The actual inflation rate each quarter is this average plus or minus a term that depends on the unemployment rate, U, relative to the NAIRU, assumed to be 6 percent. This term is (6/U(-1) - 1). It implies a Phillips curve slope of one-sixth a quarter, two-thirds a year at U = 6 and has the usual curvature.So, I think the answer is no. A faster monetary contraction leaves the 8 quarter lag of inflation in place, so you'll get even bigger unemployment and not much contraction in inflation. If someone else wants to redo Tobin's simulation with the actual 81-83 inflation, that would be interesting. But it is a bit tangential to the central story, 1984. You can also see here in the highlighted passage (my emphasis) how adaptive expectations are crucial to the story.

Now, let's be fair to Tobin. Yes, as quoted by Steve, he came out in favor of "Incomes policies," which used to be a nice euphemism for wage and price controls, but have an even more Orwellian ring these days. But Tobin also wrote, just following this graph,

This is not a prediction! It is a cautionary tale. The simulation is a reference path, against which policymakers must weigh their hunches that the assumed policy, applied resolutely and irrevocably, would bring speedier and less costly results. There are several reasons that disinflation might occur more rapidly. When unemployment remains so high so long, bankruptcies and plant closings, prospective as well as actual, might lead to more precipitous collapse of wage and price patterns than have been experienced in the United States since 1932. Moreover, the very threat of a scenario like figure 6 may induce wage-price behavior that yields a happier outcome. A simulated scenario with rational rather than adaptive expectations of inflation would show speedier disinflation and smaller unemployment cost, to a degree that depends on the duration of contractual inertia, explicit or implicit.My emphasis. Now, having seen only one big Phillips curve failure in the 1970s, it might be reasonable for policy-oriented people not to jettison their entire theoretical framework in one blow. And this Tobin piece, using adaptive expectations, does incorporate some of the lessons of the 1970s. In the 1960s, Keynesians used a fixed Phillips curve. Friedman famously pointed out that it would not stay fixed -- but even Friedman (1968) had adaptive expectations in mind. For policy purposes it might make sense to integrate over models and adapt slowly, an attitude I just recommended in present circumstances.

You can see Tobin clearly seeing the possibilities, and clearly seeing the conclusions that we would come to after seeing the "happier outcome." That he had not come to these conclusions before the fact is understandable.

That contemporary commentators should forget or obfuscate this history, in an effort to resuscitate a comfortable, politically convenient, but failed economics of their youth, is less forgivable.

I don't want to fully endorse the classic resolution of 1984. Lots of other things changed, in particular deregulation and a big tax reform in the air. There was a lot of new technology. Financial deregulation was kicking in. We may find someday that such "supply side" changes were behind the 1980s boom. And we may jettison or radically reunderstand the Phillips curve, even with the free expectations parameter to play around with. It certainly has fallen apart lately (here, here and many more). But ISLM / adaptive expectations as an eternal truth just doesn't hold up. It really did fail in the 70s, and again in the 80s.

PS: The chart using actual inflation FYI